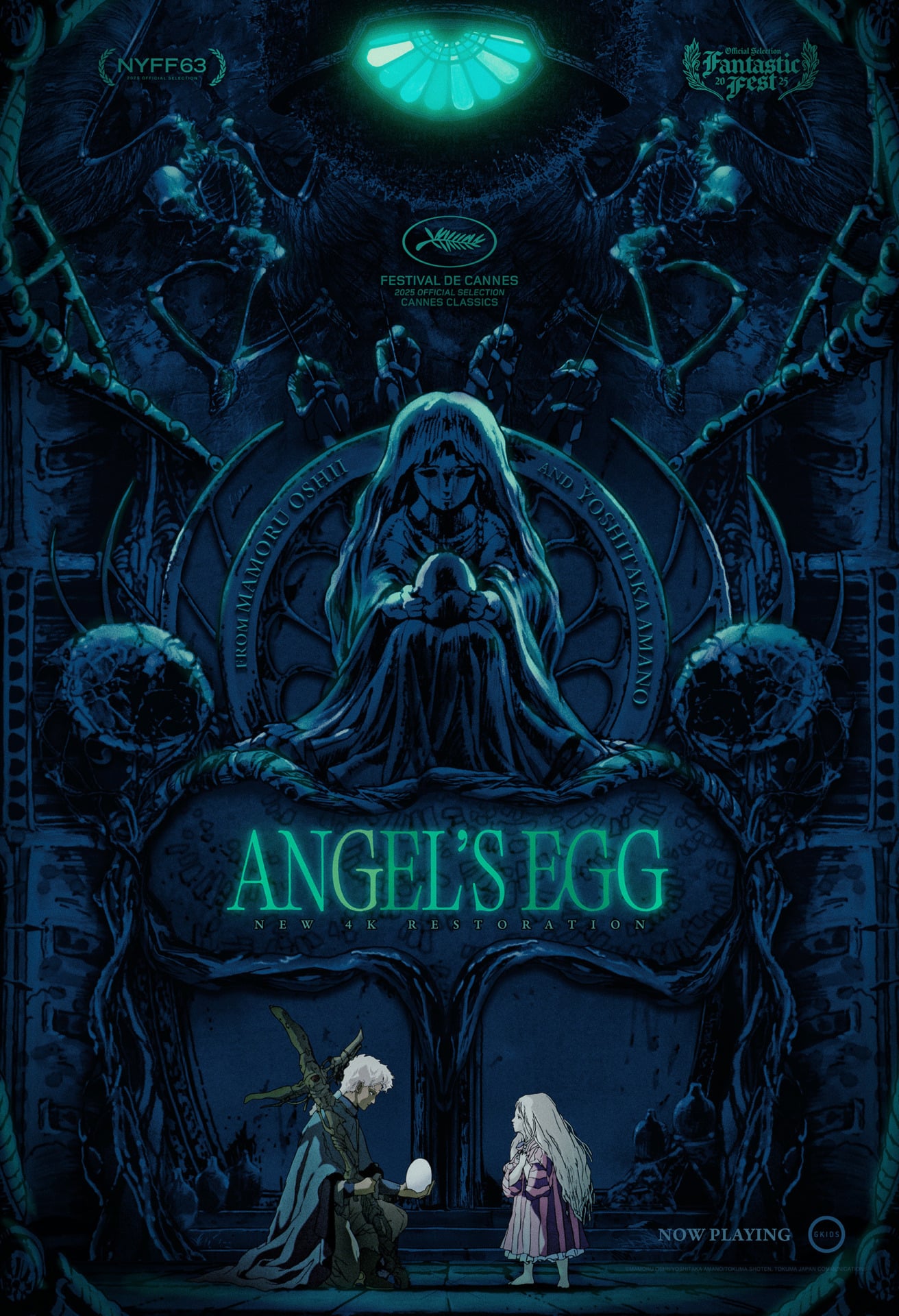

In a world where celebrated creatives tend to take influence from Mœbius and Giger, Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg feels right at home in the latter camp. Yet, somehow, it also supersedes all influences and has earned the reputation of a cult classic original video anime the industry will never see the likes of again.

Forty years later, it’s returning to theaters, restored in 4K by Gkids and exposing a new generation to a lauded paragon of the anime industry. If ever there were a film synonymous with “show, don’t tell,” while verging on the unparsable yet deeply felt, it is Angel’s Egg—a work long whispered about in anime forum corners as something everyone must experience at least once, and a gem that feels virtually unspoilable even decades after its release.

While it historically exists as a film that bombed and left its director out of work for a spell, only later ordained as a surreal masterpiece, what makes Angel’s Egg such an albatross of an OVA is that it is celebrated yet rarely spoken of. No one can readily say what Angel’s Egg is “about,” as if it were some hallowed-ground anime meant to be experienced rather than explained (because it is). That hushed reverence makes it a difficult film to recommend (and to review) because, despite how narratively thin the “what” is, the “why” is what lies beneath the tip of that iceberg and is what makes it a seminal film.

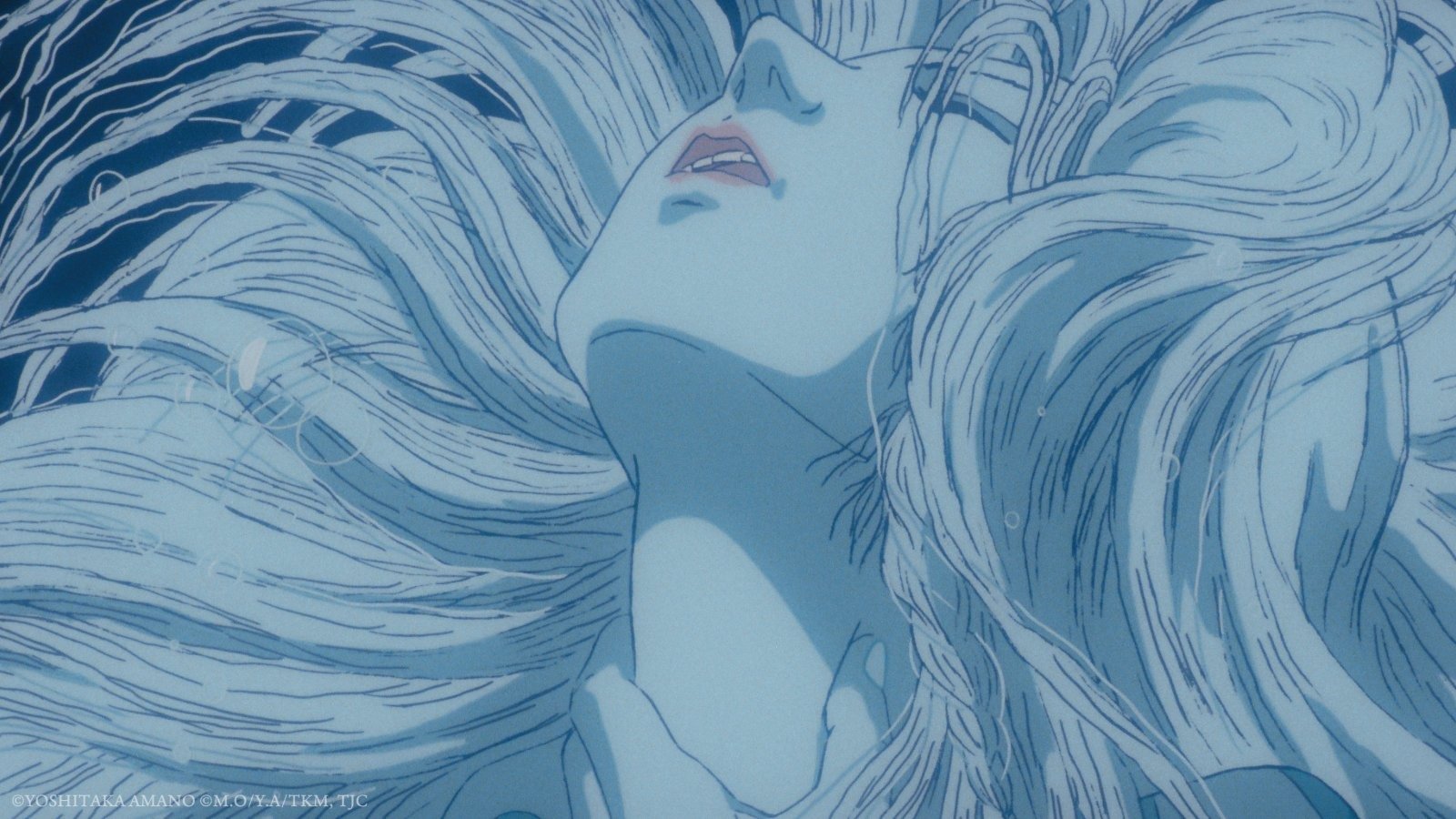

Angel’s Egg follows a nameless girl who awakens like a listless Victorian child, the kind who might rest her head on a windowsill while absentmindedly nursing blossoms from the ivy crawling up her Rapunzel-esque castle wall. Except here, instead of ivy vines, she tends to a giant egg, hidden and kept warm beneath her billowy pink dress.

Her whole existence revolves around protecting this egg as she wanders through derelict, cold-blue cityscapes, collecting glass vials and other receptacles and noshing on mason jars of jams she pilfers from abandoned houses for no discernible reason. She’s a meek little creature, clearly on some pilgrimage from on high. Along the way, she encounters a boy, also nameless, who seems to have arrived on what must be Earth from a spaceship that’s wholly Giger-esque. He’s clearly seen some things, burned out from the unsung weight of them, yet behind his dead fish eyes lingers an insatiable curiosity—the same question the audience shares: what is the deal with the egg? So he follows her.

Their journey is one of rare words, exchanged instead through perturbed or apathetic glances, all underscored by Yoshihiro Kanno’s haunting score. What happens after that feels as open to interpretation as it is inevitable, with her tepid imploring of the boy to promise not to take her egg and the boy, lugging around an auspicious “could definitely split a giant egg”-sized staff, never offering her so much as a grunt that could be taken as him saying, “Sure thing.”

And there lies the mesmerizing nature of Angel’s Egg: its spoken lines wouldn’t fill more than two pages of dialogue, leaving silence and imagery to carry the weight of its vexing, all-encompassing, visual presence.

It’s almost disarming how Angel’s Egg is so hushed yet quietly thunderous. That tone is established immediately in its glacial, slow-moving opening: you sit (quite literally in the dark) in solitude before a black screen with no score, wondering if the film forgot to start. It didn’t—it’s simply in no rush, taking you down the scenic route to wherever it’s fixing to take you. Once you move past that hump, its avant-garde yet matter-of-fact beauty takes hold, and its 71-minute runtime flies by. The film practically beckons you to sit still in fascinated anticipation for even the smallest thing to occur on screen, a miracle born of its methodical, indulgent, downright lackadaisical pace. It’s the kind of rhythm that would invite you to stop and smell the flowers—except this derelict earth is bereft of Mother Nature, save for the promise of whatever lies inside its bowling-ball-sized egg.

Director Oshii—of Ghost in the Shell fame—and studio Deen were almost terrifyingly bold to have crafted a film in 1985 with so little dialogue yet such trust in the audience to follow along. That choice is what gives the film its unparsable “all vibes” feel. A feeling that was enough to make fellow anime statesmen like Hayao Miyazaki pause, reportedly remarking that he “appreciates the effort, but it is not something others would understand” and that Oshii “goes on a one-way journey without thinking of how to get back.” Yet it’s precisely through this lack of narrative clarity, through its lush, painterly artistry—wispy Yoshitaka Amano illustrations fully committed to film—that the work sings.

In 2025, the concept of an anime film that permits itself the luxury of leisure is just as alien as it was 40 years ago. Still, set against contemporary movies of the moment, which often lead with dazzling (at times illegible) visuals to overwhelm audiences, Angel’s Egg pumps the brakes and simply vibes, luxuriating in its immaculately crafted, overtly bleak, and oppressive atmosphere. It’s the kind of film where gestures and micro-expressions carry a ton of weight. A curl of the lips, a mistrustful stare—all tiny cues that speak volumes between two companions who rarely speak but remain bound together.

Its artistry extends to the film’s ornate, impressionistic backgrounds, where the gurgle of a brook is juxtaposed with the strained chugging of machinery as tanks crawl through towering buildings on cobbled roads, which feels like being pulled into the undertow of the anime’s visuals. Angel’s Egg is rife with ephemeral moments audiences wouldn’t usually pause to appreciate in their daily lives. Yet, here they become wide-eyed at the resplendent vestiges of beauty in a desolate world. All the while, two strangers wander through this grim world as the rest of the film plays like a lucid dream where statuesque men spear fish the shadows of whales dancing about the skyline of its entombed city.

Angel’s Egg is the film equivalent of a one-way mirror, a surface onto which you project meaning and, in perpetuity, discover new things. Some will run with the Noah’s Ark analogy of its derelict world, others with its alien, militaristic invaders as allegory—fodder for the inevitable YouTube explainer with red arrows promising “details your plebeian brain missed.” But the film resists being chewed and digested that way. It is Lynchian in its refusal to be solved, a work that invites interpretation without ever demanding it.

Its imagery suggests environmental ruin—nature long fossilized, eons gone, with only two living figures wandering what remains. At its center lies the egg, a Schrodinger-like entity: perhaps harboring the promise of life in a lifeless world, maybe nothing more than another hollow shell mirroring the emptiness around it.

While its setup is as straightforward as it is ambiguous, its ending opens into a vastness of interpretation, teeming with meaning yet refusing to settle into one. Is it an environmentalist call to action? A religious shakedown of hubris and humanity’s folly? Or a secret third thing—something ineffable, tugging at the spirit but beyond articulation? Whatever it is, Angel’s Egg is nothing short of a religious experience, a once-in-a-lifetime beauty of visuals and music lying in wait that everyone owes themselves the chance to witness at least once, if only to understand the unstatable miracle of what anime, at its most daring, can be.

Angel’s Egg is playing in theaters now.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.